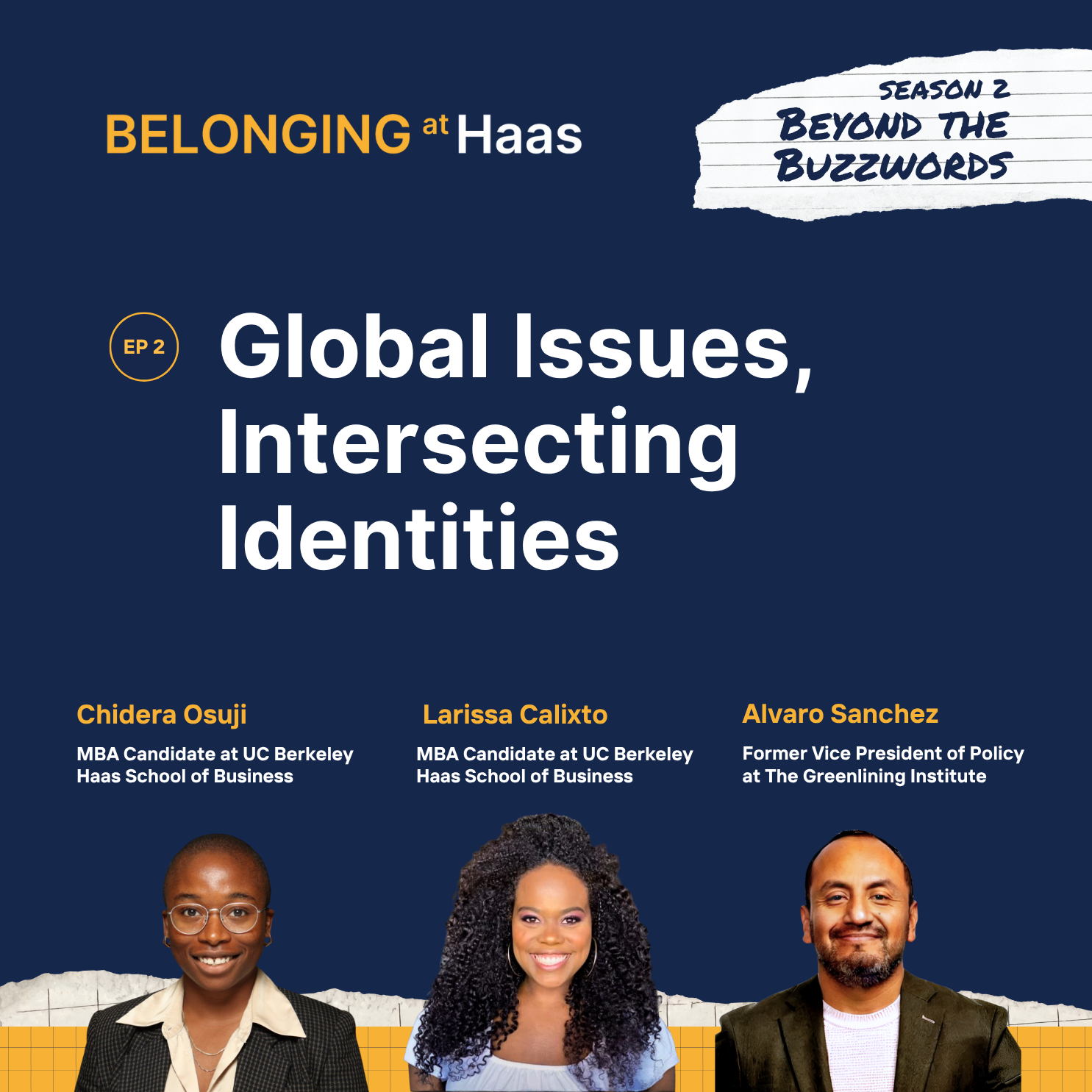

As this season of Belonging@Haas continues, this episode’s host Jenny Linger interviews Chidera Osuji and Larissa Calixto, MBA candidates at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, about how diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and belonging (DEIJB) intersect with climate and sustainability issues. Then Jenny checks in with Alvaro Sanchez, former Vice President of Policy at The Greenlining Institute, for his thoughts on the discussion and insights from his experience in the field.

This conversation covers both personal and global perspectives, with Chidera and Larissa sharing from their own experiences in sustainability and social impact, and how these topics are intertwined with inclusion, justice, and belonging. Alvaro contributes from his work experience in climate policy and explains the importance of equity in building a prosperous future. Together, they explore the importance of representation and the critical need for inclusive leadership in approaching global issues.

Belonging at Haas Podcast is produced by University FM.

This episode was also produced by Jenny Linger.

Developed in partnership with the Haas MBA Student Government Association.

Episode Quotes:

Chidera opens up about how her inner narratives and the nuances of belonging held her back from taking up space.

[22:06] Chidera Osuji: I constantly thought to myself, everyone around me is so much better. They’re handling everything. They’re able to keep up [with] the academics. They know what’s going on. Why am I here? And like someone made a mistake, and everyone must be aware of it because I feel that so deeply I’m not supposed to be here. And that feeling has followed me in a lot of spaces, including at times at Haas. Again, not because of anything anyone says, but because those are some of the narratives I’ve internalized based on what you see in media or how other people seem to carry themselves. And sometimes you anchor onto the details that are not the ones that are meant for you to succeed. And I’m trying to reframe and anchor on the ones that would support me and reaffirm my existence or my being in a space. But that’s a journey that’s going to take a long time, and I’m trying to, in this season, lean into community to affirm me and also build that internal affirmation, internal validation, because a lot of harm can be done when you look externally, within reason, because we are living within the systemic realities. But at the same time, there’s a lot of internal work that can be done to set you up to deal more effectively with the realities that exist outside of yourself.

Changing the world starts with taking care of yourself.

[27:51] Larissa Calixto: From my lived experience working in grassroots movements and in the nonprofit sector, I came to realize that trying to change the world while ignoring my own well-being was not sustainable many, many times. And that I could not pour from an empty cup. So I don’t really know how to do this. I think it’s easy to say but hard to do, but I’m learning, and I think we really need to set boundaries, protect our joy, our rituals, build community, and have the confidence that the problems won’t disappear overnight. But if we take care of ourselves along the way, we can better keep contributing for the long run.

Why bridging people matters in finding the solutions we need.

[33:33] Alvaro Sanchez: We always have to be thinking about bridging because it’s not just about making it easier for someone else to cross to another path. Sometimes it’s about bringing those that have the solutions closer to the problem so that we can actually get to the solutions that we need.

On speaking up and taking space for yourself and others when none exists.

[38:51] Alvaro Sanchez: Space often is not going to be made for you. You’re going to have to create it yourself. But that’s why you need a strong network, for that network to be cheering you on and be telling you that you have something important to say and that you should be able to say it. I think try to avoid being in silos and echo chambers. It’s not helpful when everybody around you is telling you that’s the right answer all the time. Some level of doubt, I think, is helpful for the work that we’re trying to do. Real diversity is critical for us to be successful, and diversity doesn’t happen just because everyone around us is telling us the same thing. It actually happens when someone around us says something different.

Show Links:

- Jenny Linger | LinkedIn

- Chidera Osuji | LinkedIn

- Larissa Calixto | LinkedIn

- Alvaro Sanchez | LinkedIn

Transcript:

(Transcripts may contain a few typographical errors due to audio quality during the podcast recording.)

[00:00:02] Jenny Linger: Hey, everyone. I’m your host, Jenny Linger, and you’re listening to Belonging at Haas, the B School MBA podcast. This is a Berkeley MBA student-led podcast focused on diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and belonging. We share student perspectives and expert advice in candid dialogue, tapping into new viewpoints and engaging in open, honest conversations that foster a welcoming and inclusive environment.

Belonging at Haas is a part of a Race Inclusion Initiative course project at Haas School of Business. Developed in partnership with the Haas MBA Student Government Association, and together we’re committed to creating a more inclusive and equitable community. So, let’s get into it.

Too often, DEI gets reduced to corporate jargon, and that’s why this season, our theme “Beyond the Buzzwords” takes a critical look at what DEI really means for leaders, organizations, and our community at Haas and beyond. We explore why representation, both formal and informal, matters, how global challenges amplify identity-based inequities, and what it takes for business schools and companies to foster the growth of truly intersectional leaders.

We’ll break all of that down first with our two MBA student guests, Chidera Osuji and Larissa Calixto, and then with our expert guest, Alvaro Sanchez. Who, as an urban planner, spent a decade as Vice President of Policy for the Greenlining Institute, shaping over $8 billion in California climate investments targeted at priority communities.

This episode, titled Global Issues, Intersecting Identities, aims to explore and deepen our consideration of how, while sustainability, including environmental justice, is inspired, informed, and often led at the grassroots level by Indigenous and communities of color, the most prominent leaders and figures in climate and sustainability are still overwhelmingly white.

Consider the moment in January of 2020 at Davos when Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate was cropped out of a press photo when posing alongside white activists, including Greta Thunberg. This incident impactfully revealed to the world how visibility and representation are not just symbolic. They have real consequences for those whose voices are amplified and those whose voices are silenced. And this isn’t an isolated dynamic.

The erasure or sidelining of marginalized identities across contexts, including on business school campuses like ours here at Haas, beg the question, ″How do we see and value inclusion as being integral to the architecture of climate solutions?” I’m excited to introduce two MBA students and leaders in the Haas MBA, Chidera and Larissa. They are with us here today to share their experiences in sustainability, climate, and social impact, both here at Haas and in their prior careers.

Welcome, Chidera. Can you start us off by sharing a little bit about yourself?

[00:03:07] Chidera Osuji: Sure. Thank you so much for that wonderful intro, Jenny. My name is Chidera Osuji. I am currently a second year at Haas School of Business, concentrating in sustainability. Prior to being at Haas, I have worked in a few different fields. Shortly after completing undergrad, I worked at a corporate law firm for two years, did a rotational program, thought about going into law, and ultimately decided that I was more interested in getting into communities and speaking about some of the things that affect the built environment.

So, I pivoted to an urban design and landscape architecture studio, worked in operations, thought about going to design school, saw the work that designers and architects, and realized that my skill set might be better suited to zoom out and work closer to consumers instead of in infrastructure. And so, I decided to come to business school as a way to unite some of those disparate interests that I had and that background that I had within other fields, specifically, consumer packaged goods and retail. I’m most interested in circularity within sustainability.

So, a simplified way of saying that is the “reuse” part of “reduce, reuse, recycle,” but really interrogating ways that we can create economies out of mending, repair, and extending the life cycle of the things that we own. That connects to a lot of topics that I’m sure we’ll get into today, but I’m excited to be here to speak with Larissa and Alvaro. Thank you all for having this conversation.

[00:04:33] Jenny Linger: Amazing. Thank you so much, Chidera. Larissa, we’d love to hear your story too. Can you share a little bit about yourself?

[00:04:39] Larissa Calixto: Yeah, sure. Thank you so much, Jenny, for having me. And thank you for having me, too, Chidera. My name is Larissa Calixto. I’m a second-year student at Haas, and I’m from Brazil, from São Paulo. Before Haas, I spent eight years working in the social impact sector as part of the founding team of Teach for Brazil, where I led business development and finance. Teach for Brazil is part of the Teach for All Global Network, alongside Teach for America and other programs in more than 65 countries.

And I came to Haas because I wanted to deepen my understanding of systemic change. My passion and purpose are to create a world where everyone, no matter their identity or background, has a fair starting point in life. And I realized that education was a powerful lever for that, but also that the problems we face are broader and more complex than what I imagined.

Here at Haas, I’m focusing on sustainability, social impact, and systems thinking. My hope is to become a bridge between sectors, being able to speak different languages and help design collaborative solutions while also building a successful career.

[00:05:58] Jenny Linger: Amazing. I feel so blessed to have both of you as classmates, and thank you for being here today. You’ve, kind of, already introduced us a little bit, but Chidera, with your Nigerian roots, and Larissa, with your Brazilian roots, I’d love to hear what parts of your backgrounds have shaped who you are today.

[00:06:16] Chidera Osuji: Yeah, definitely. My family is from Nigeria. I actually was born in the United States, in Georgia, lived here for three years, moved to Nigeria for three years, came back, and my older siblings also came with me. I, kind of, lived this multicultural upbringing from birth, of course, and lived in a really diverse environment in Atlanta, where I grew up for the most part.

And so, being Nigerian, being second-generation Nigerian, was very influential for the way that I saw everything about the world and the way that I still conceptualize things. And so, I really love the phrase that you used earlier, Larissa, about bridge building. I think, to a certain extent, all of us who are interested in sustainability and interested in DEI are bridge builders. That’s the only way to do the work that we’re doing, or at least to view some of what we’re doing, because we’re sitting at the intersection of so many things.

And so, that’s all to say that I think being a second-generation immigrant influenced so much of where I am today. For example, in undergrad, I studied one of my majors was Ethnicity, Race, and Migration, a really long name, but it was essentially thinking about the different structures of power and flows of resources historically that have brought people to be where they are today.

And a big part of that was not solely focusing on the academic or corporate professional way of thinking about those things, but focusing on the individual and the individual story, and the specific nuances that affect us. What does it mean when we look at an entity, like, as one homogenous corporation or one homogenous organization, and how can we be more creative if we were to tease out who the individual stakeholders are within that? Understand their motivations, in order to be more effective and to really speak to people on a human level to make those changes happen.

Having grown up, how I grew up, with some of the cultural influence, has allowed me to understand that people are not monolithic, and we hear that often, but it’s easy to hear that and harder to act on it.

[00:08:33] Jenny Linger: It makes a lot of sense and is a really key takeaway in life to understand the context around every person’s situation and dynamic. Larissa, I’m curious to hear you share the shape of your background per your experience.

[00:08:48] Larissa Calixto: Yeah. I was born and raised in São Paulo, that is the largest city in Latin America, in one neighbor called Capão Redondo. And I think this starting point of my life really shaped everything that I believe in, all the journey that I’ve been living throughout my career, and my personal life as well. In the ’90s, when I was a child, this neighbor was ranked by the United Nations as the most dangerous and violent neighborhoods in the world.

So, growing up as a Black woman in that environment completely shaped how I see the world and how I’ve been navigating. Like, growing up in this situation, I always believed that education could change my life, and it did. As I gained access to better education through scholarships and other racial support me, I noticed that many of my peers, my family, my colleagues, my friends, and people from my neighbor didn’t have the same opportunities that I was having access to. So, I think that was my first real understanding of inequality.

I saw this firsthand in my personal life, and then I understood that this was a systemic issue. And I was growing up thinking about pursuing education and going to university. At the same time, I saw many friends and neighbors lose their lives or end up in prison or live without hope because of drugs, violence, and lack of a sense of possibility.

So, those experiences made me deeply committed to equity. And I’m an accountant, and I worked for a little bit in the private sector, but was also always involved in, like, volunteer and movement, and social movements. And when I shifted my career to the nonprofit sector at Teach for Brazil, I started to add new layers to my identity, because Teach for Brazil collaborates with the Teach for All Network.

So, I was having access to more people outside of Brazil. I was starting to learn English. I didn’t grow up speaking English, and I actually started to learn English to apply to business school a few years ago. So, I started to understand the complexity that I saw firsthand in my environment, now globally. And here in the U.S., being Latina is something that is really present in my daily life, and it’s an identity that really shapes my way of communicating and relating with people here. In Brazil, that was not something that I used to think.

So, yeah, now that I am developing myself as a global leader and interested in, like, wicked problems globally, I see more clearly how all of my identities and this intersectionality has shaping my ways of looking at the problems, and also my ways of looking at the solutions.

[00:11:57] Jenny Linger: Yeah, thank you so much for sharing so powerfully here. How have these experiences shaped the way that you think about climate and social solutions in the world? What paradigms, values, ideas have been most influential to you?

Larissa, will you start?

[00:12:14] Larissa Calixto: To be honest, before Haas, I didn’t think much about climate change. My activism was always around social issues. So, education, access to culture, sports, health, wealth distribution. But coming to Berkeley opened my eyes. This is a place, a state, and a program that is at the forefront of climate discussions, and I’m learning how to deeply connect climate and equity on another level.

In Brazil, we are already seeing floods, wildfires, and extreme weather affecting the most vulnerable communities globally. The countries that contribute least to emissions are often the ones most affected, so that’s injustice. And during my summer internship, I went back to Brazil, and I was working in a consulting company, and I had the opportunity to work on a project related to the COP conference.

[00:13:15] Jenny Linger: Amazing. Yeah, they are these parallel efforts to really have a long-term sustainable solution for sure. Chidera, what about for you? What are some of the ideas and values that have been most influential?

[00:13:31] Chidera Osuji: Yeah, definitely. I will focus in on a few examples that come to mind. The first one is just thinking again about my cultural background and living in Nigeria for a few years, and visiting since then. I’m always struck by how my family members, and even my dad, he actually used to be in the Nigerian army, he retired when I was in high school. So, there was a long time where my family was here, but he was still in Nigeria.

But whenever he would come back to the U.S., or whenever I would visit, there’s always such an intentionality about extending the life cycle of things and ensuring that the resources that we do have been used to the last drop, in a very literal sense. Part of that is economic, part of that is social, and some of that is also just the orientation that, culturally, people have around what it means to have a resource, to have a gift, to be endowed in some way.

And I don’t mean like a big endowment, I mean, just, like, what you have at your disposal is so important and so precious. And so, for me, I’ve seen my dad, like, try and reuse things in the house. He’ll come up with a new function for something that you think should be gone, should be out of the house. And sometimes it’ll be frustrating, but there is so much creativity and care for self, care for family, care for community, that goes behind that. And I’ve come to value over time and have tried to practice in my own life.

And that’s an example of a thread, culturally, that I’ve followed in my professional career and is part of my interest in climate and sustainability today. And what that creativity of thinking about how long and intentionally you can use something? One thing that we do can cascade and affect ourselves and our communities much further than we realize. There’s only so far we can go with the current systems that we have without interrogating them and thinking about the small things that we can do, and the big things that we can do to change them.

[00:15:36] Jenny Linger: Wow. It’s very powerful. I love that you drew out that intermingling of care and resourcefulness as being, yeah, reinforcing each other. Thank you for sharing that. I guess, reflecting back to the case of Vanessa Nakate that I mentioned in intro, I’m wondering from both of you, have there been times when you felt left out of the picture, whether literally or figuratively? And on the flip side also, where have you found hope in more inclusive spaces, communities, or colleagues?

[00:16:07] Larissa Calixto: So yeah, I felt like Vanessa many, many times is clothed and not feeling included and perceived by my peers. And I think being a black woman in Brazil was very critical in that matter because in Brazil, we are about 60% of blacks and browns in the population. Is the country with the highest number of black people outside the African continent. But unfortunately, less than 5% of the business leaders are black and brown. So, I think our social elevator is broken. We don’t have social mobility. OECD made the study in 2018 about social mobility, and the conclusion was that in Brazil, it takes nine generations to move from poverty to middle income.

And in my personal story, that happened in three generations. My grandfather was born right after the abolition of slavery. Abolition, so unquoting, because that was not really the true. It took a long, long time for this to be really over in Brazil. And in three generations, I’m now the first black president woman admitted that has in a program that has in the history. So, that was a journey… I’m really proud of this journey, but it was really, really intense and really exhausting, and really exuding as well.

At my university in Brazil, when I did my undergrad in business, I was the only black woman among 600 students in my year. And being the only one was a constant in my life, whether at school, at work, in leadership spaces. So, I readily saw anyone who looked like me or shared my lived experiences. And here in the U.S., I’m glad to share that my experience has been different from my previous experiences. For the first time ever in my education, I’m not the only black student in the classroom, and I never imagined the impact that this would have on me.

Honestly, it opened me up to build community instead of isolating myself, and also to recognize both the structural and individual dimensions of belonging, because, yes, still I sometimes feel like an outsider because I don’t share the same networks, resources, and experiences as many of my peers here in the MBA. But over time I’ve learned to see myself not only as an outsider, but also as someone who, despite coming from an underprivileged background, now have the chance to sit in the same classroom and access just the same resources as my peers.

So, I feel that the community is being more welcoming to me, and I’m also allowing myself to not isolate myself and build community. So, as I’m feeling like this very first-time feeling of inclusion here at Haas, that’s why also I serve as VP of DI for the MBAA, because belonging has always been deeply personal for me.

[00:19:27] Jenny Linger: Yeah. That’s beautiful, Larissa. Thank you so much for sharing. I remember when I first met you, in some of the first conversations, you were both obviously this, like, super bright, beautiful, confident person, and you also revealed this vulnerability of, like, still feeling, like, do I belong here? And, like, am I an imposter? And so, I’m happy to hear that this experience has been building that sense of belonging for you.

[00:19:55] Larissa Calixto: Yeah, it is. Thank you very much.

[00:19:57] Jenny Linger: Yeah. Chidera also would love to hear from you about times that you felt like you’ve been left out of the picture, and also where you’ve found more inclusionary spaces, communities, or peers.

[00:20:12] Chidera Osuji: Thanks so much for sharing that. Similar to what Jenny said, when I first met you, when we had that little pre-MBA trip exploring Southern California, I got the same impression of you being just so bright and having so much to share and being such a light. And it’s been wonderful seeing you, as Jenny said, like, find some community at Haas. And excited for that to keep happening. And very grateful to have you and your perspective here, and all the experiences you bring.

Yeah, because you’re pushing so many people to think differently about all, kinds of, things. From my side, I think it’s a combination of things for me in that there have been several situations in life where I felt, like, not necessarily any explicit factors were leaving me out of the picture, but because of my positionality and some internal narratives I have about myself, I have excluded myself from spaces. So, for example, I went to Yale for my undergraduate degree. There were many students of color there at my time there, which was very great. And we had resources available to us.

And at the same time, this was the first time I had been in any environment like that. My mom was a nurse. My dad was in the Nigerian military, but this was the first time navigating the educational system in the U.S. I went to public school in Georgia, like, a very average, good public school, but not one where I was taught how to speak up in a seminar or one where you understand colloquially what the value of networking is and getting to know your peers.

And so, I was very in the books, very like, ″Okay, I need to get a good grade because this means that,″ but not understanding what the bigger picture was. And also, some extracurricular groups I was in, I constantly thought to myself, everyone around me is so much better. They’re handling everything. They’re able to keep up the academics. They know what’s going on. Why am I here, and how can I… like, someone made a mistake, and everyone must be aware of it because I feel that so deeply. I’m not supposed to be here.

And that feeling has followed me in a lot of spaces, including at times at Haas. Again, not because of anything anyone says, but because those are some of the narratives I’ve internalized based on what you see in media or how other people seem to carry themselves. But you’re not listening to other people’s internal monologues. You can only hear your own, and you can only glean like what your perception of the reality that you’re facing is.

And sometimes you anchor onto the details that are not the ones that are meant for you to succeed. And I’m trying to reframe and anchor on the ones that would support me and reaffirm my existence or my being in a space. But that’s a journey that’s going to take a long time. And I’m trying to, in this season, lean into community to affirm me and also build that internal affirmation, internal validation, because a lot of harm can be done when you look externally, within reason, because we are living within, like, the systemic realities.

But at the same time, there’s a lot of internal work that can be done to set you up to deal more effectively with the realities that exist outside of yourself.

[00:23:31] Jenny Linger: Wow. Very powerfully said, Chidera. I love that point of coming back to connection, to refill your cup and brighten your light. From here, I’d like to know what do you think is the most important thing for our classmates to understand as they step out into climate sustainability, social impact fields, especially those with the desire to work on projects and investments that will impact huge and even global populations, Chidera?

[00:23:59] Chidera Osuji: Yeah. There’s a few things, but I think I’ll focus on the balance of zooming in and zooming out. There is a great deal of information and personal story, and narrative that you can get when you are curious about the individual people, individual stories, and specific factors that have influenced people in their lives and their trajectories. And at the same time, looking at the structural systemic realities that have influenced how they have landed in a certain place, or how you have landed in a certain place.

And so, I would encourage, and I’m also working on this actively, my classmates and peers to think about those two levels and work hard to see how you can bring them together. Because I think change can only happen when you are both zooming in and focusing on the small details and zooming out to understand how they are a product of, and also independent of, their larger context.

[00:25:02] Jenny Linger: Great, thank you, Larissa.

[00:25:04] Larissa Calixto: Yeah. First, I would like to thank you for being such important pieces of my belonging journey here at Haas. I really, really agree with Chidera on that, on systemic view, I would highlight three things, three advices that I feel, as Chidera mentioned, are also advices that I’m giving to myself in this journey. I think first I would say humility, because, I mean, there is so much we don’t know and so many people have been working on those issues for decades now in grassroots movements, nonprofits, government, philanthropy, businesses.

So, I think it’s important to recognize that yes, we are eager to contribute and bring our bright ideas, but also, it’s important that we recognize that we should honor that work and learn from it as we build on it with our innovation and our desire to make change. I think another one is really related with systemic view that Chidera mention. So, I really believe that many past mistakes in climate and social solutions came from treating problems too narrowly. And I really believe that real change requires seeing the big picture and understanding how issues connect.

One book on that that I love, and I would really strongly recommend, is Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows, which I used in one of my past classes, systems thinking. I also strongly recommend this class, as I was really interested in learning more about systemic change. I think that really changed my way of thinking on those wicked problems.

And I think a third, but not least important one, is self-care. From my lived experience working in grassroots movements and in the nonprofit sector, I came to realize that trying to change the world while ignoring my own well-being was not sustainable in many, many times, and that I could not pour from an empty cup.

So, I don’t really know how to do this. I think it’s easy to say, hard to do, but I’m learning, and I think we really need to set boundaries, protect our joy, our rituals, build community, and have the confidence that the problems won’t disappear overnight. But if we take care of ourselves along the way, we can better keep contributing for the long run.

[00:27:55] Jenny Linger: I love that, Larissa. Well, thank you so much. Larissa, Chidera, this is amazing talking with you. And now I’m super excited to bring in our expert guest, Alvaro Sanchez. Before we dive in, Alvaro, would you tell us a little bit about your background and the identities that shape your perspective?

[00:28:16] Alvaro Sanchez: Yes, absolutely. Thank you so much, Jenny, for the invitation, and it’s been a pleasure and an honor to listen to Larissa and Chidera share about their background. My background, I’m a kid from Mexico City who came to the United States when I was very young, and I’d been shaped by being an immigrant, by being an undocumented immigrant here in California.

And someone who just was finding, kind of, his way, trying to live out the dreams of my parents, which was to have a better life for ourselves. We didn’t leave Mexico because we didn’t like it or we didn’t want to be near our families, but we left because we didn’t have economic opportunities there. Or at least not the ones that my parents saw being able to leverage to be able to provide the, kind of, life that they wanted for their family.

So, we came to the United States. I went to high school in East LA. I went to community college for a couple of years, and once I was able to go to a university and be able to pay in-state tuition, which was a change in law that happened during the time that I was able to do that, I went to UC Santa Barbara for my undergrad, where I got a degree in sociology.

Post that, I, you know, probably had like about 20 different jobs. I did everything from being a lifeguard to being a display artist, actually at the Urban Outfitters that was right across the street from UC Berkeley’s campus, that is no longer there. But I was the window display artist there. I worked at Rasputin Records down on Telegraph as a cashier, and I did all these jobs because I was undocumented, so I couldn’t do much of anything else. I could just do the jobs that I was able to get.

And eventually, when I became a legal resident, I started doing work on social change, you know, campaigns. So, I became an affordable housing organizer in San Francisco. And when I was doing that, I realized that I wasn’t the best organizer and really wasn’t my passion. But what I was really passionate about was cities and how they get planned and how they get executed. So, I decided to pursue a master’s in planning at the University of Southern California, and eventually I found my way towards working on climate policy, which is what I’ve done over the last 10 years.

And I have worked at the Greenlining Institute, where I was the VP of policy there. And about a year ago, I left that job and have been focusing my time since on trying to figure out a new path forward for climate policy here in California, one that is really meeting people where they’re at, and one in which we remain to be ambitious on fighting climate change, but we’re even more ambitious on trying to solve the economic transition that we are experiencing in, and doing so in a way that doesn’t leave people behind, which I think is a really tall order to try to do, but it’s an important one and one in which we have to really think about it.

[00:31:01] Jenny Linger: Wonderful. Well, we’re honored to have you here with us as well as we continue the conversation. And after hearing Chidera and Larissa’s stories and experiences, I am thinking of a favorite and beautiful quote that I’ve read of yours, which is, ″Equity is not an obstacle, it’s a foundation for prosperous future.” So, I’m curious now, what stood out to you from what maybe what Chidera and Larissa shared, and when have you also personally felt most inspired or empowered in your work?

[00:31:32] Alvaro Sanchez: Absolutely. I mean, I was so impressed by both Larissa and Chidera, and their stories resonated so much, and I jotted down so many things that they said because it really described my experience. I felt like I understood it because I felt the same things in my experience, and I really think it really relates to this question about equity and how… I mean, many people think of equity as an obstacle, but it’s really not.

It’s just an experience of people that are coming from different backgrounds and different places, that when combined together and when we approach things not thinking about, like, the one system that we’re trying to address, but the systems that make up our lives, really just makes us so much stronger. So, you know, I like that Chidera talked about the winding path to an MBA. I just described a winding path to climate policy of myself, and I feel like in the past, I used to say like, ″Oh, it was not a linear path.”

Well, nothing is linear. There are no linear paths. Nature doesn’t have lines. Nature, it moves all over. I also heard them talk a lot about bridging and themselves being bridged, but also them, like, you know, like Larissa talking about Jenny and Chidera, like, you all have been bridges for Larissa in her experience here in Berkeley. Being a bridge is so important because, like, we have to connect sometimes, like, populations that are not involved in the conversation. We sometimes have to connect people that are two opposite ends of a solution that haven’t yet connected.

So, we always have to be thinking about bridging because it’s not just about, like, making it easier for someone else to cross to another path. Sometimes it’s about bringing those that have the solutions closer to the problem so that we can actually get to the solutions that we need. I also, kind of, just like extrapolated a lot of awareness from both of them. Like, they were aware from a very early stage in their lives about the privilege that they have. Even when you grow up in an under-resourced community, there is sometimes privilege within that, and the awareness to be thinking about sometimes, like, yeah, you may feel like that sense of like, ″Why am I here?”

There’s an awareness there that’s happening that I think could be both good and it could be bad, but just the awareness to have about your environment, about what people need, about the observations that you are making about life. For me, personally, what I get most inspired by, honestly, is just people’s journeys. I just find that so uplifting to know that people waking up every day… does something my dad says, like, ″Getting out of bed is probably the hardest thing that we all have to do on a day-to-day basis.”

I’ve been fortunate and blessed to have seen colleagues of mine, community leaders that I’ve worked with, elected leaders that I’ve worked with, just have a journey and be successful at what they do and make change. That inspires me because it’s just like the will that it takes to be able to achieve those outcomes, knowing that you’re confronting systemic barriers over and over again. It’s just beautiful.

Similarly to how I just heard and felt uplifted by Chidera and Larissa’s stories, like, it’s not easy to do what they’re doing and to get to where they’re at, but it’s inspiring to know that they took on that work and landed here. And then just personally, something that I think inspired me is work that I’ve done in communities, bringing resources to those communities so that the people that live in those places and have experienced the most pain are architects to the solutions that they want to implement in their communities and are able to see that through and are able to see that change.

And are able to feel proud about the fact that the work that they are doing is towards creating positive outcomes in their communities. I’ve been blessed enough to see that firsthand, and yeah, that’s the type of fulfillment that I’ve always wanted to have in this, kind of, work.

[00:35:16] Jenny Linger: That’s incredible. Yeah, it definitely resonates for me that in your last point on your engaging with communities, that the ability to be at service is such a key point of restoring energy, in bringing that fresh energy to every day that you feel more connected to your community. Recently, you’ve emphasized the fragility of our sociopolitical ecosystems in parallel with ecological ones. From your perspective, what pitfalls should we avoid and what levers can we pull, both here in the MBA programs and in the broader climate and sustainability space?

[00:35:51] Alvaro Sanchez: Yeah, I had to think about this a lot when you first mentioned it, because I wanted to come up with an answer that was, you know, very maybe technical, and it’s like these practices. But at the end of the day, I just had to come back to, like, just what we’re doing right now, me getting to meet you all. Ultimately, these are human problems. We’ve contributed to these problems, and it’s going to take us to solve them.

So, the more that we’re in community, the more that we can be building bridges, dialoguing, addressing sometimes hard truths, talking about trade-offs, that’s the biggest lever that you can pull. And honestly, in this environment, it is probably some of the most difficult work, particularly when you need to talk to someone who all the identities seem to crash with yours. And we see that so much more now. I have been guilty of this, where, if I see the signals that someone that I’m talking to, it’s all the identities that just doesn’t seem to match up with the ones that I bring to the table, it’s been harder for me to listen to them.

It’s been harder for me to take it seriously, and from the start, whatever they’re saying, I’m already thinking that it’s not the right answer. So, I’ve really been focusing over the last several months on needing to slow down, needing to listen, needing to let my guard down a little bit more, and I may not agree with the person, but I do have to get better being able to talk to someone who sends all the signals that are not the ones that I should be listening to.

For the most part, the people that I talk to, we are able to see eye to eye on so many things. And I think building that community and expanding that network and maybe, like, casting the net a little bit further out is something that I think is really powerful and part of the solution of what we need to do moving forward.

I think another thing that I would definitely say for folks to do, particularly people of color, and I heard it a couple of times already, is that we need to speak up and take space. People of color often come into these communities with the idea that our ideas don’t matter as much, maybe that we don’t have the background or experience that contributes to the conversation, and our voice gets really, really low.

I would say train yourself to get out of that habit. You need to take space. Space often is not going to be made for you, you’re going to have to create it yourself. But that’s why you need a strong network for that network to be cheering you on and be telling you that you have something important to say and that you should be able to say it. I think try to avoid being in silos and echo chambers. It’s not helpful when everybody around you is telling you that’s the right answer all the time. Some level of doubt, I think, is helpful for the work that we’re trying to do.

Real diversity is critical for us to be successful, and diversity doesn’t happen just because everyone around us is telling us the same thing. It actually happens when someone around us says something different. I think we have to avoid being overly reliant on technology, on finance, and policy. Sometimes we make all this work about those things and not about the human interactions that people have, and we have to be able to, like, not overly rely on those solutions.

And I think we have to avoid minimizing the problems and the solutions that we bring to the table. Everybody gets energized about tackling big problems, so I think the problems that we’re trying to tackle are really big, and we should never really minimize them to say that there are other things that are more important or more critical. Our problems are big, just as others are big as well, and I think we do a disservice when we minimize them.

[00:39:24] Jenny Linger: Yeah. Thank you so much. You nailed it. It’s the connection, compassion component that really can be born out of creating really diverse environments, as you’re saying. I guess I’m thinking about this moment that we’re in when DEI is being erased by name. How do you think organizations, communities, and individuals can meaningfully create more inclusion and leadership opportunities that actually strengthen equity and resilience, given these new constraints?

[00:39:55] Alvaro Sanchez: I think we really have to stay focused on what is our end goal and not the current environment. That’s a condition. That current environment is going to change. It changed previous to this, during COVID and George Floyd’s summer, when we had an open opportunity to really make strides on diversity, equity, and inclusion. I think at that time there was a lot of momentum towards getting commitments to that. I used to always preach, it’s not about the commitment, it’s about the practice. Are people willing to practice a different approach to achieve the outcomes?

And because we stayed committed to the goal, we were able to actually identify a lot of places that were not committed to the practice. But we were able to utilize that time to be able to continue to say, ″Well, what’s our goal?” Our goal is to change systems, laws, and practices. ″How do we do that?” Let’s make sure that we put out materials and frameworks, and resources for the people that are really committed to this to be able to take advantage of it.

Maybe you have to change the way that you describe the work. Maybe you have to change the nature of what the work looks like, but you don’t compromise your values. You don’t say, “Well, everyone deserves the same shot.” That’s not equity. Ultimately, sometimes you’re just going to have to speak out, and you’re going to have, you know, call attention to the problem. And when something is racist, and right now, a lot of things are, you just have to call it out and be able to stand firm on the fact that you’re calling out the injustice that’s happening in the world.

So, it’s a difficult time. Obviously, it’s not easy to be able to do this work, but we can absolutely continue to do the work, and as anything, you just have to adjust your strategy, your tactics, and stay committed with the long-term goal of what we’re trying to achieve.

[00:41:39] Jenny Linger: Yeah, that’s right on. And maybe this was actually an ideal segue to ask you a little bit about the way you’ve been reframing your vision for an energy transition around a climate-smart economic initiative. Can you walk us through that framework and how your experiences over the last decade have shaped it?

[00:41:58] Alvaro Sanchez: Well, I mean, I think at the beginning of this year, when we knew that the environment in California around climate policy was going to change in very big ways because of the Trump administration, I had the opportunity to just really reflect on how much progress the state of California had been able to make around solving the climate crisis.

And for me, more importantly, how are we doing about addressing the inequities in the state? Because the idea was that we would be able to both tackle the climate crisis and the inequities through the climate policy that California was advancing. And that reflection resulted in me saying, ″We’re not doing good enough.” And it didn’t matter that we had a Trump administration, even under a Harris administration, those same problems would’ve continued to exist here in California.

So, it didn’t really matter that we had this dramatic change in federal government. The conditions had already been baked in, and it was because of the approach that we’ve been following over the last 10 years for climate policy in California. So, even under a Harris administration, I would be saying the same thing. We need a new pathway. We need a new approach.

We need to address the economic transition that we are currently experiencing, and we need to bring in the resources, the policy levers, the appropriate government capacities to deal with this economic transition, so that we can address the climate crisis that we’re in, but in a better way, address the inequalities that the state continues to be dragged down by. So, the climate-smart economy is one that, in our opinion, delivers broadly shared prosperity, economic resilience, and local community benefits.

It’s one that responds to the reality that we need an economy-wide transition that drives sustainable and inclusive economic growth, cuts daily costs, and creates businesses in every region. And one where climate solutions are fundamentally aligned with the global scale of the climate crisis, not merely delivering greenhouse gas emission reductions within the state.

[00:44:01] Jenny Linger: Thank you. As you’ve noted, this movement is dependent upon us believing and trusting in each other, building that relationship. You’ve also had the need to reimagine “normal” in air quotes. If you could leave us with one vision of a new normal, what would you want it to be?

[00:44:19] Alvaro Sanchez: One that I’m really focused on right now is a new normal for what it means to govern. I think we need to reimagine what governing and government look like, and we have to build new, kinds of, civic infrastructure that allow us to actually deliver on that future that we want to see. I think that there’s so many opportunities to leverage some of the work that’s happening in communities, where communities, out of necessity, have had to come up with new ways to address everyday issues that sometimes it was the responsibility of government to do.

We have to rebuild trust in government and institutions because they are absolutely critical to creating the, kind of, playing conditions so that everyone can succeed. The private sector cannot be completely running wild and running free. The climate crisis, in many ways, is baked in because of private sector activities and running an economy on fossil fuels. So, a new normal for me would be a government that you can trust in, governing that is open to debate, discussion, disagreement, but ultimately making the best decision for us to move together.

And a new normal would be that we are able to deliver on the everyday things that people need to thrive, good housing, clean air, clean water, good energy, reliable broadband, good education, just the simple facts of life that give people the opportunity to succeed and to thrive, and that people have faith that those things are going to be delivered for them.

[00:46:03] Jenny Linger: Such an important message coming back to the basics.

[00:46:08] Alvaro Sanchez: Jenny, can I say one last thing?

[00:46:10] Jenny Linger: Oh, please.

[00:46:11] Alvaro Sanchez: I heard earlier Chidera say a line, and I, kind of, just wanted to flip it a little bit. I know that a lot of us struggle with the confidence of being in this space, and a lot of us sometimes feel like we don’t belong. But I would really encourage us to cling to the details that are proof that you are a success. Because sometimes we cling to the details that make us doubt that, but you got to cling to the details that are telling you, ″You belong here. This is your space. You earned it.” So, I just wanted to share that with you.

[00:46:39] Jenny Linger: Well, thank you so much, Alvaro. We’re going to close this out here. Really, a heartfelt thank you to Chidera, Larissa, Alvaro for sharing your time, stories, and wisdom with us today. This has been such a meaningful conversation that I’m so excited to share with our classmates and beyond. And so, that concludes our episode for today, in our second season of the Belonging at Haas Podcast, Beyond the Buzzwords. If you’ve missed our first episode, DEI: Myths and Misconceptions, you should definitely check it out.

Finally, huge thanks to our listeners for tuning in, and be sure to check out past episodes and join us next time as we continue amplifying the diverse voices and perspectives that make the Haas community so vibrant. Thanks again, Larissa, Chidera, Alvaro. Such a pleasure.

[00:47:27] Larissa Calixto: Thank you very much.

[00:47:29] Chidera Osuji: Thanks for having us. It was great talking to all of you.